I would like to talk to you about decision.

Decision is, you will discover, one of the fundamental points of indecision, and one of the fundamental reasons why people are sane or insane. Decision.

You see, decision is a short way of saying choice. And choice, of course, is the keynote of self-determinism. To determine anything, you must have the choice to determine. Choice to determine means that you must have the power of decision.

Automatically, you will discover — automatically, in any case — that the one thing that is holding up beingness is indecision, a maybe.

In any engram that presents itself to be run — in any engram that presents itself to be run — there is a maybe: two choices which are relatively balanced, and their even balancing makes an irresolution.

Now, there's a great deal to do with time in decision. Decision and time have a lot in common. When we have clean, clear decision, we have clean, clear time. And when we have an indecision, there is an unclarity about time. if you are trying to decide anything and having a difficulty in trying to decide that thing, the root of its trouble is time. Not even necessarily data; it's time. There's a time hangup there somewhere. And if you look for that back of the data, usually the data becomes needless.

Decision: The basic decision that life makes, that theta makes, is "to be or not to be." Shakespeare's famous line: "To be or not to be: that is the question." Hamlet was in very, very bad condition that day. He was hung up on the squarest maybe that anyone can be hung up on.

If you see someone facing a new job, a choice of whether or not he's going to continue with his old job or take a new job, you may think that he is resisting change or a lot of other things, and so on. Re's not anything. I mean, he is hung up until he decides one way or the other on a beingness situation. So that any beingness situation where you had a "to be or not to be" on a case becomes itself the most aberrative situation.

Running an engram is really, basically, only necessary until the preclear has reached, of his own volition and evaluation, the decision he didn't make. He's found the maybe in his life. He's found that maybe. And having found the maybe, it is clearly enough in view so that he can resolve it or evaluate its importance, and the rest of the engram will blow. It'll disappear-become completely unaberrative.

Postulates are important only because postulates are the root material of decision. That is to say, you have the decision and you make the postulate to reserve the decision. "To be or not to be" is action or inaction, existence or no existence.

Actually, there is no such thing as a black-and-white decision. Aristotelian logic would like you to believe that there is such a thing as a syllogism: A is to B as B is to C, then A is to C, or something of the sort. This is very easily confused into A equals B, and B equals C; therefore A equals C. This isn't true. But it was a desperate effort to see if one couldn't get over the awful hurdle of yes-or-no. Syllogism: It gave you a way to reason so that everything didn't keep coming out in the middle.

Aristotelian logic is based upon black-and-white solutions, really. You'll find today the mighty and powerful churches of the world believe in black and white for their people. They tell their people it's black and it's white; it's sin, it's good. There is no intermediate step here. It's one or the other.

Well, it would be very fortunate for all of our sanities if decisions could be made like that. If we could say it's a black decision, which is to say "not to be," or a "to be" — a "to be," a "not to be" — if we could say just those two and resolve them very cleanly and clearly, we'd be fine.

Unfortunately, if you will look under the Logics in the first section (they are printed in the "Handbook for Preclears" and some other volumes) you'll find that gradient scale of logic, and it demonstrates to you that there is only relative decision. Relative. Just like there's only relative self-determinism. And there's only relative yes and no.

There are a million grades, a billion grades, of yes. There are a billion gradient points on the scale of evil, and a billion on the point of good. Things are only relatively bad and relatively good.

Relative beingness, then, is what we are trying to decide. And when a person comes close to the center of the scale and hangs up, that is what happens: he hangs up. Now, why does he hang up at that point? It's very simple why he hangs up at the point. Decision has much to do with time. if you have decision, you have time; if you do not have decision, you do not have time. Now, it doesn't matter whether you decide "not to be" or decide "to be." If you're hung up in the middle between "to be" and "not to be," you have immediately forfeited time, because the middle of the scale is zero time. "To be" or "not to be" — and in the center there, zero time. So when a person hits a maybe he starts worrying about it.

What is worry? Worry is constant, irresolute computation — constant computation on a certain point or a certain problem. That's what worry is; that's what anxiety is. Anxiety, you see, is fear added in. "I'm not going to be able to resolve this." Then worry becomes anxiety. "I can't resolve this," is just worry; "I'm not going to be able to resolve it" — well, that's anxiety.

If you want to treat worry and anxiety, you can slug into a case with just these points, these tenets I'm giving you right now, and just tear the case to pieces. And the fellow, oh, he feels good afterwards. He's got everything all resolved. Trouble is, the most aberrative decisions were generally made when a person was in very bad shape — the worst ones. There is the decision of going on living or not going on living in this body. You can find the places where he makes this decision. "All right, I won't give up. I'll go on living, I . . . guess. No, I'll give up. Uh … there's no reason to go on living. Yeah, I'd better go on living. No, I guess I can't go on living."

"To be or not to be," you see?

It'll hang up a whole operation. "Now let's see, to go on living I have to have this operation. If I have this operation, it'll probably kill me." He never gets a chance to decide this. Somebody takes him by the scruff of the neck and lays him out neatly on the table and puts the mask over his face. That's why your childhood operations — tonsillectomies and so on — are particularly grim. They affect the individual terribly because a child never has a choice.

They can go around and say, "Now, Johnny. . . now, Johnny, you want your tonsils out, don't you, Johnny? Now, it's up to you to decide now, Johnny, whether or not you want your tonsils out. But of course, if your tonsils don't come out, you'll keep on having these nasty old colds. But you've got to have 'em out now, and I just want you to decide . . ." All they're trying to do is get him to agree, they're not getting him to decide. And the eventual thing is that poor little Johnny goes on the table.

By the way, the first thing that happens to him is his central control post, that stands up above the other two, generally flicks out during one of these operations. If you want to find somebody's control post, you generally go back through his childhood operations. Because he didn't have any power of choice over the thing.

It's my belief that in a good society every child ought to be equipped with and taught to fire a sawed-off shotgun.

It's like the hunter: He goes out and he shoots a doe or a duck or something of the sort. He gets a big — he feels big about this, you know? The thing to do is to give the duck or the doe or something, you see, give them a shotgun too and then teach them how to use it, and it'd come up to a parity level. Well, it ought to be that way with kids. They ought to have a chance. But they don't have a chance, so there isn't any chance of deciding this until we've solved this body problem, and we can solve that so we don't have to worry about this anymore.

But the point I'm making is, is decision is sanity and indecision is aberration. Now, you can't say "to be" is necessarily sanity or "not to be" is necessarily insanity. You see, those aren't the scale of sanity to insanity. Because you see, you can always make the decision to be insane. You see, it doesn't say what you're deciding to be; it says that you're deciding. But what is aberrative is whether or not one is able to decide, and the degree that he's capable of decision establishes his sanity, self-determinism, power of decision.

Many people have gotten hung up on the idea of willpower. It was very fashionable a few years ago, particularly, to go around telling people they didn't have willpower, they should use their willpower, or something of the sort, without defining willpower. Wonderful operation. Actually, if you said that these people should rehabilitate their decisional power, you would have a much different picture. Willpower, decisional power: now you'd have a point there.

Any time an individual is put under duress, it is the individual's effort to make a decision about the duress. If the duress is very heavy and makes only one decision possible, well, he falls into that category. It's not terribly aberrative. He's been overcome, he will feel degraded, he'll feel a lot of other things, he isn't free, but somehow or other he can struggle out of this sooner or later.

The way to drive somebody insane is to convince them that they should have a yes, and then convince them equally they should have a no. And then convince them they should have a yes. "Now, Bessie, you've got to make up your own mind, it's your own free choice of whether or not you get these new shoes. Now, do you want black shoes or white shoes? Of course, the white shoes are going to get dirty a lot faster then the black shoes. Now, which do you want? The black shoes or the white shoes? Oh no, Bessie, you don't want the white shoes, you want the black shoes. The black shoes are much easier to keep polished and they'll go with your new dress. Hm-hm, yes. Oh, they're how much? Oh, uh, huh, well, you want the white shoes, Bessie. Uh . . . Bessie!"

It's a wonderful mechanism. I recommend it. I recommend it to governments and sergeants. It reduces individuals to just complete weakness because it's chaos!

We used to draw this tone scale, you know, straight up and still draw it straight up, and it's very, very easy to graph that way, but it's not quite true. It's a curve, if you add decision into the line. Actually, the point of 1.5, if you want to know the truth of the matter, is the center of the scale. Because if you make a person make a decision and then unmake the decision, then make the decision, then unmake the decision and make the decision, you'll eventually make MEST out of him. And 1.5, you've got him holding there, you see? You've got enough confusion so he's holding there, and you'll stick him there. And then there's a method of dropping the whole curve down to apathy and he becomes MEST and he's part of the material universe and you don't have to worry about him anymore!

All right. There's an actual scale, though, on decision itself. And this is something for you to remember and something for you to use in processing. Never forget to ask your preclear where the indecision is in the incident. Never forget to ask that preclear that. "Where's the indecision here?"

Now let's put this in terms of motion. We can understand it a little easier.

Now, all of the first Axioms have to do with a static called life and counter-efforts and efforts. You have this chain-fashion affair whereby in comes the counter-effort, the fellow turns around and uses it as an effort. In comes the counter-effort, he turns it into his effort and uses it. That is what life is doing. That's what you're doing. You get a counter-effort and you use it — counter-effort and you use it.

And as long as you can use these counter-efforts, why, you're fine. I mean, it isn't aberrative to get shot at. What's aberrative is not to — yeah, to get hit! — not to shoot back.

It isn't even aberrative to get hit, actually; I mean, so you get killed. So what?

You know, at Pearl Harbor there was — I think it was a tug, lying across from Battleship Bow. And the Jap planes came in, and the high command up there, you know, they were all on the ball and everybody was on the qui vive and FDR was on the qui vive and the War Department, Navy Department — everybody was on the qui vive — and they're all ready for these planes. So the planes came in and knocked the fleet out. And they had made a decision, by the way. They were not on a maybe. They had decided they could lick the Japanese fleet in five weeks. Huh! So they didn't go any further than that. Making a decision prematurely sometimes is quite effective in destroying oneself, but it's not aberrative.

All right. Here came in these Japanese planes over this little tug and into Battleship Bow — wham! wham! wham! And actually, these planes were passing close enough over this little tug so that they were almost knocking its stack off. And the officer in charge had a full crew aboard. And naturally, a tug, it was on a standby, it wasn't on liberty like everybody else had been sent. So here sat this small tug with a full crew.

The percentage of psychos and war neuroses and so forth who turned up out of Pearl Harbor was enormous, because they had received a motion they couldn't use, you see? They couldn't do anything about it.

And this officer grabbed a few bins of potatoes as his crew came on deck. And he grabbed these bins of potatoes and he had his men standing there throwing potatoes at the Zeros. And he didn't have a single psychotic aboard.

The crew was perfectly cheerful. And immediately after the action, they patched up a few bullet holes in themselves and went to sea merrily to pull things off the bars and the reefs, and so forth.

Why? They were getting a motion, you see? They were getting attacked and they were attacking back. And even though it was just a token attack, it was quite effective as far as morale was concerned.

Now, if you receive a motion, you should be able to use the motion. Your indecision comes only when you refuse to use the motion you have received. And anybody who has an engram in restimulation (including the human body, which is after all just an engram) — and mark this well — you have in that person simply this: a motion which he will not use. That's the only one he's stuck with — the only one he gets stuck with.

A counter-effort comes in — wham! "Well," he says, "so they hit you in the jaw. Well, that's something." And — doesn't matter when — a few days, a few weeks from then, a few years from then, a few lifetimes from then, he all of a sudden remembers getting hit in the jaw, and a fellow's standing there and it seems to him that's the motion he's supposed to use. So wham! He hits the fellow in the jaw. He's healthy.

The fellow that isn't healthy is standing there, you see, and the fellow hits him in the jaw. And he says, "Shouldn't do something like that to me," and he goes on for a few weeks or months or lifetimes (short span of time). Guy comes up — here's a situation where he's supposed to hit somebody in the jaw — and he says, "I think I'll hit him in the jaw! Nah, I wouldn't do a thing like that." After that he gets a somatic. Why? He's called the facsimile up to use and then he hasn't used it. He has a counter-effort which he is unwilling to use. And when he has a counter-effort which he's unwilling to use, it attacks him.

The only way you aberrate people is keep them from using their counter-efforts. You get them out and you do things to them, and then you don't permit them to do it. You say, "Under no circumstances should you be able to do this."

You take little Oswald and you take him down and you kick him a couple of times and you say, "You little brat," and so forth. "Now get out of the house." And little Oswald comes in a few days later — you notice children will do this — and he'll take a look at you and he'll say, "You brat!"

And you say, "You should not say that, Oswald. You must treat your grownups with respect." You fixed him, right there. He's all set; he's going to use this counter-effort — it wouldn't bother him very much and he's going to use this — but you don't let him. That's the way you aberrate him.

The way you can aberrate a whole society is take and put a police force over the top of them that permits them to be arrested and manhandled, given traffic tickets and sent to jail and pushed around and taken into courts of law and everything else, and then you don't let the guy do it himself. He then has a sensation of being handled, pushed, handled, pushed, censured and so on. And he gets all of these counter-efforts and he can't use any of them. Because the police object to being shot and pushed. I don't know why, it's only sporting.

But this country out here was a good, solid, healthy country until they got their first reformer. It was. Everybody used to carry an equalizer — called it an equalizer. But somebody came up to you and said "You blankety-blankety-blank," you just shot him! I mean, it was simple, justice, so on. So people after that were careful about calling you a blankety-blankety-blank. Till one day you called somebody else a blankety-blankety-blank, he drew faster than you and you're dead. But, it's an interesting game. They played it with wild abandon.

Down to the south, down here at Tombstone, they've got a whole hill there where people played it with abandon. But at the same time, the country was pretty healthy. Guys walked tall, they walked very tall. They didn't drive down the street saying "I wonder if that cop saw me pass that traffic light," see? Big difference between that.

I'm not, by the way, beating the drum for uncontrolled, unlicensed action in an aberrated society.

The society gets into a big maybe. It comes down tone scale to a point where an individual may or may not be ethical. And the second the society gets to a point where it looks at an individual and doesn't know where he is on the tone scale and whether — or whether or not he is going to be ethical, that society has to muster unto itself morals and police power, and suppress all individuals because some might not be ethical. And the second this happens, you get an aberrated society, because everybody is hung up on a maybe. "Is this fellow honest or isn't he honest?" "Is he going to be irrational about the thing or isn't he?" I mean, it's just maybe, maybe, maybe, maybe, maybe, maybe. So people start thinking.

Thought could be said to be the resolution of maybes. Computation and its purpose depends upon the resolution of maybes. As you go way up tone scale, you get less and less and less maybes, and you actually do less and less and less computing, and you do more and more and more knowing. That's quite important.

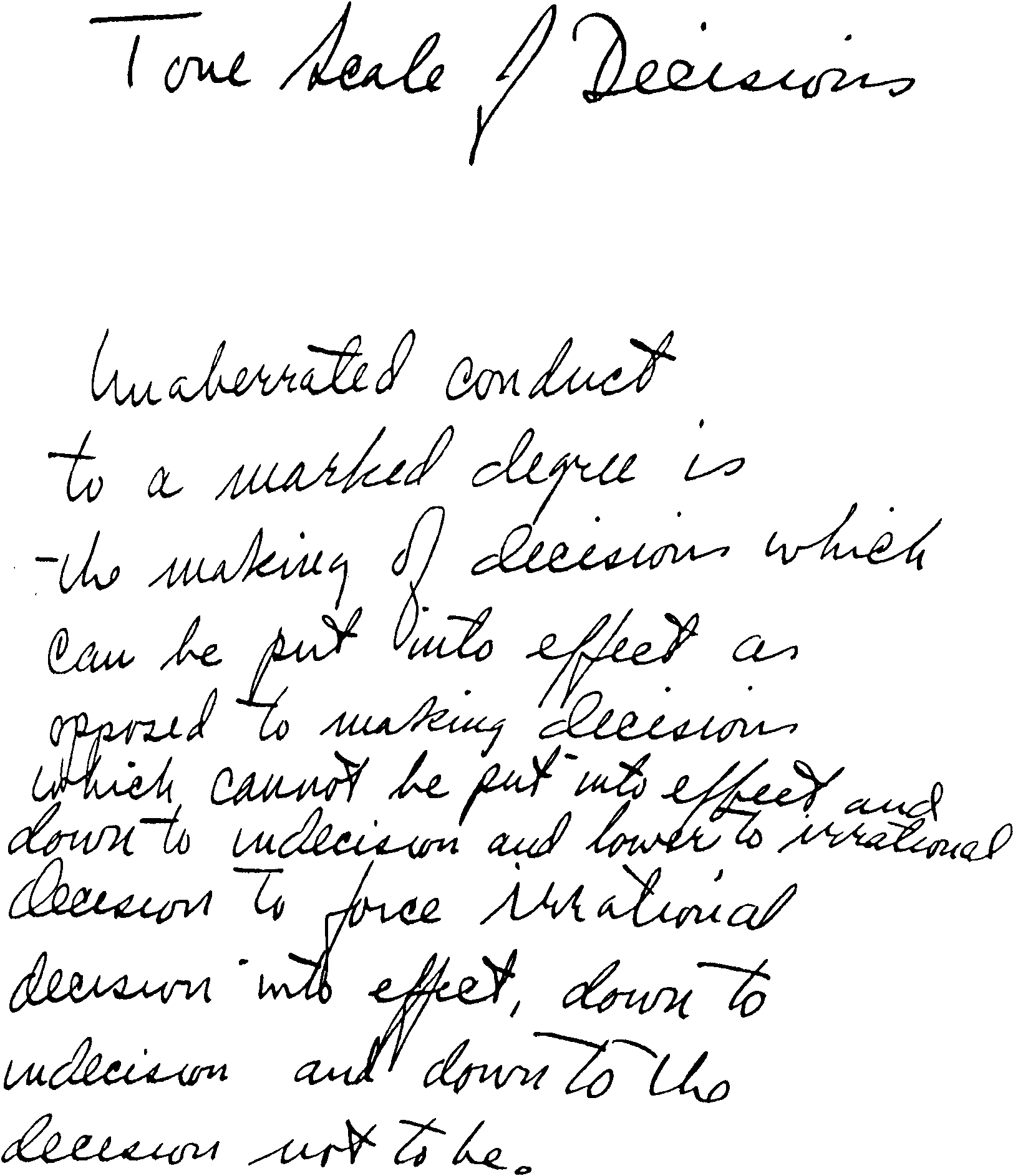

There is a scale here of decision, which I will draw here. Unaberrated conduct to a marked degree is the making of decisions which can be put into effect, as opposed to making decisions which cannot be put into effect, and down to indecision, and lower to irrational decision to force irrational decision into effect, down to indecision, and down to the decision not to be. The Tone Scale of Decision, in other words, is that scale. [See Ron's handwritten notes on the Tone Scale of Decision in the Appendix.]

Now I'll draw that scale for you. Up here we have "to be." Up here, when you make a decision you put it into effect: decision equals effect. When you're making decisions to put them into effect, believe me, you're cause. (I'm going to talk the second talk this evening on cause and effect and how it applies to "be" and "not to be," how it applies to going up the whole dynamics.) But this is very simple. If you put things into decision, you're going to be a cause and you're going to make an effect, very quickly.

Now, as you come down scale, you just simply come down to this level: You make a decision here — this is well down scale — that can't be put into effect. So you get a decision that can't be effected. You're making decisions, see, but they can't be effected. It's irrational, you see? The fellow says, "I'm a — I think I'll be president." Well, he can think he'll be president all right. He's made a decision that he's going to be president, but he can't put it into effect. In other words, he has not evaluated the rationality of his decisions. Up here, he makes a decision, it's a decision that can be put into effect. He doesn't keep overmaking decisions or undermaking them. In other words, he's doing a proper estimation of his decision. And then we get down here, this is very mild effect, but here we have an indecision, see?

And by the way, it's very, very interesting that low on the tone scale we have people who put indecisions into effect. Did you ever know anybody that put indecisions into an effect? Well, they exist. Believe me.

This is getting way down the line here: We get decisions to force irrational decisions into effect. Where is that on the tone scale? What is it?

1.5. That 1.5, they're wonderful at that. They're always making decisions to put irrationalities into effect. The second you show them an irrationality, they'll put it into effect; if you show them a rationality, they won't put it into effect. It's as much as your life's worth. As a matter of fact, if you want a 1.5 to act, what you do is demonstrate that what you want to do is irrational, and then they'll make you do it. You see how that is? You show them what you want to do is completely irrational; then they'll make you do it. That's a fact, it works.

Then we get down here into indecision. And that is about 1.0. That's "Am I going to stay here or am I going to run?" Fear is just below this, you see? But that's the borderline of fear right there: indecision.

And now we come down here finally to apathy, which is decision not to be.

Here is your enthusiast — people like me, always making decisions that "can't be put into effect," you see? Saying, "All right now, we — what we're gonna do is — is get this and we're going to make this, and then get right in there. And everything's fine."

And somebody points out to me, "Yeah, but we haven't got the two million dollars that it takes to do that."

And I say, "Oh, well, all right." People have a hard time with me.

Well, there's your tone scale of decisions. And you can actually take a preclear and look him over very thoroughly and you can find out what he's deciding to do and you can say where he is on the tone scale. You can also spot him on the tone scale and then predict very, very well what that individual will decide.

Now, in interpersonal relations your problem is simply this: the problem of other people's decisions. That actually is the core of interpersonal relations. These people, by being certain things, become very antipathetic to your survival and happiness. By deciding not to be certain things, they become helpful to your survival. And again, by deciding to be certain things they become helpful, and deciding not to be certain things they become very unhelpful. You see how that would be, then? You're continually faced with people's decisions.

Now, there is why individuals who are low on the tone scale are so very hard to be around: It's this decision scale more than anything else.

I told you last night that ARC — affinity, reality and communication — add up to computation. They are understanding. The three together will actually make mathematics. They are computation; they are understanding; they are a gradient scale of knowingness. A, R, C. So ARC would also be beingness, wouldn't it? As you go up the line on ARC, you get into beingness. And therefore, clear-cut ARC resolves into decision. And this is a tone scale, again, of ARC and decision. So that you get your A, your R and your C: Here we have "to be," decisions can be effected, so forth, and we have affinity. Well, believe me, when a person is up there on the tone scale, they decide "to be" on an affinity level, it's really a big "to be." Affinity. They just — wheeoww!

On agreement, remember that they're cause or they are in parity with other people who are capable of being cause. You start agreeing with people who are way up there to the top of the tone scale and you're not going to be in bad shape, you'll be in good shape.

You start agreeing with somebody down here, you're agreeing with fear so that fear becomes reality. And if you start agreeing with "not to be" — down, not to live, not to act well and so forth — done yourself a very, very bad trick. This is sympathy right in here in this band. You've agreed that it's all right not to be.

You say, "Poor fellow. Poor fellow. It's all right not to be," and the only thing wrong with that is, is you've gone into agreement too low on the tone scale, which is sympathy. All right.

Now, as far as communication is concerned, believe me, it's relatively easy to communicate with somebody who is way up at the top of the tone scale. It is very simple to do that. In the first place, anybody up that high, theoretically, is not communicating to any large degree through MEST. The person is actually communicating very, very straight, and it's pretty easy to hook up to. As a matter of fact, when that is hooked up to on a communication level, it has a deaberrative effect upon the individual. Down here when communication is hooked up to, it has an aberrative effect, because they'll start throwing you maybes and so forth.

There is ARC on the basis of decision. Practically all that is really wrong with any preclear is basically, if he's in bad shape, he's decided to be the things he shouldn't be, or he's decided not to be the things he should be. This isn't too bad. Might have said that a little bit wrong. I mean, you know lots of people who seem to be getting along fine, and, gee, they've decided to be the damndest things. And you know people that are getting along fine who have decided not to be, perfectly … Some fellow, he decided not to be a millionaire. See? That's what he decided. That's all right — that's what he decided. Of course, you won't go into very close agreement with him if you think the thing to be is a millionaire. But that's just a — just a matter of decision.

What's wrong here is the person who — "Am I gonna be a millionaire, not gonna be a millionaire? Is it good to be a millionaire? No, millionaires get into danger every once in a while; I'm not to be a millionaire. Well, the communists are liable to shoot us, so therefore it's better not to be . . . Now, that isn't good enough. We're — not got any communism over here. I mean, the thing to do is — well, it's awful hard to make a million dollars. But then on the other hand, I might make a million dollars, and I might marry a girl that had a million dollars. Well, it's a …"

Well, the way they get from there on down the tone scale is in terms of maybes. Br-r-r, br-r-r, brr. And they keep hanging up here, hanging up here. Timelessness sets in. Any preclear that's very aberrated has a bad case of timelessness. And the way to resolve timelessness is to resolve decision, and it's the easiest way to get at it I know. The way he got timeless is getting a motion and then not using the motion. He's unwilling to use this motion. He says, "Oh, that motion's very, very bad. Very, very, very bad motion. I can't use that motion!" He can't even change that motion. You can't — that's, by the way, what they call sublimation (just a hobson-jobson back into an old cult they used to have). Sublimation is the alteration of a motion into another kind of a motion — very simple.

All right. The motion comes in, he won't use it, bluntly. He says, "No!" Well, you know that's not so bad. It'll hang him up with one. That's not so bad, because he still at least said no. But the example I gave you a little while ago: the fellow gets hit in the jaw, and then a few weeks or lives or something later he says, "Oh, he will, will he? Well … " He's called the facsimile up and then hasn't used it. He said, "It's all right to use it. No, it isn't all right to use it. W-h-o-o-a!" And there it'll sit. And he'll say, "I wonder what I do with this. Well, won't go out there, won't go out there. I think I'd better go see a dentist." That's what will happen to him, because it's an unwillingness to decide on that.

He can say no and somewhat get away with it. "I've got this motion. Now I'm not going to use it at all. No, it's just bad and I'm not going to use it. I got my head cut off in the last life and I'm not going around and cut off people's heads, and that's all there is to it!" That's not so bad. But if he comes around and he says, "I got my head cut off in the last life and . . . Look how sharp that butcher knife is. Huh. No. Ha-ha. No. Yes. No. Yes."

And you'll find people running around who say, "You know, I have the awfullest time. I get near the edge of high buildings and I just want to jump off, but … " You know? So he jumped off a high building some time or other, or somebody threw him off a high building, and he's called this up. He said, "I think I'll throw him off the building." Here's somebody else — "I'll throw Og over the cliff."

Somebody threw him over a cliff once, so he sees Og standing in the middle of a cliff. He doesn't like Og; Og makes eyes at his cave girl or something of the sort. So he says, "I'll go throw Og off the edge of the cliff. No. No. No, I shouldn't do that. They passed this law in the tribe a while ago, and besides he's carrying a club with a spike on it. And if he turned around and saw me I might get hit with the spike. No, I'd better do it, though, because. . . No, I better not do it because if I — and somebody'd find out . . ." Believe me, after that, every time he goes near a cliff edge . . . Yeah. Is he? Should he? It's funny, but he keeps getting the idea he wants to jump off! Well, that's silly, because it'd kill him.

So he'll sit around the cave instead of going out hunting; he'll get lean, he'll get thin and become declasse' in the tribe, and be pointed out by the tribe elders to the little children as the thing not to be. And there he is. Because every time he walks out of the cave and every time he sits down in the cave and anyplace else, he's worrying about this cliff edge.

That's how people get obsessions. That's how they get inhibitions, so forth. If you want to be utterly uninhibited, I'm afraid you would have to use every motion that you can tap — not have to use it but have to be willing to use it. In other words, no inhibitions of any kind.

But, believe me, you've got to be pretty well up the tone scale before you start using these things, because people object. People object. Particularly when you think of the number of facsimiles which you have and what kind of facsimiles they are and some of the things that have happened to you.

Now, if you turn around and think "Gee, I — would I have to be able and willing to use any one of those, to be completely uninhibited?" But you don't even have to worry about that; you can be inhibited and still not have a body.

All right, the point is, in comes the motion. If you say, "This motion I will not necessarily hold in reserve, but I will classify: 'This motion is not to be used.'" In comes a motion: "I'll use this motion." In comes another motion, not to be used: "I consider this bad. I'm not going to use it."

You know what's very interesting about reform motions: Old lady by the name of Carry Nation one time bought a hatchet. It was an unfortunate day for the saloon keepers of America. And she went around and there was a lot of talk about bills of rights and suffrage and all sorts of things, but it started, more or less, with that hatchet.

I want to tell you something about Carry. When she was younger, she used to go down in the basement and tipple. I wouldn't like to have that known, but that's the horrible truth of the matter.

Beware of these people who come around and say, "Now, actually, we've all got to get absolutely down, wipe out, murder, stamp out and kill and throw to the lions, wolves or anything else that we can find to throw them to, the Z class of the society." Not necessarily beware of them but just know right that moment that they've taken a motion from that Z class and they've said, "Shall I? No, I better not." And then all of a sudden they say, "That maybe; that's what's driving me mad, that maybe. That's what's making me 'not to be' or 'to be' and so forth and I must do something about this maybe. And it's this maybe that's doing it. It's this maybe, I say!" And picks up the hatchet, you see, and goes to work on the saloon keepers — pardon me, it was the bottles.

I'm going to give you a little bit more about decision, just a little bit more.

In interpersonal relations, you will notice that when you have a person agreeing on a decision, you will get action. If a person agrees on a decision, you will get action if it's an action decision, and if it's a "not to be" or an inaction decision, you will also get the inaction. In other words, you get what you want by bringing to pass an agreement. This is very, very important in interpersonal relations and is actually the one problem of interpersonal relations. You'll find all arguments are based upon an inability to agree. You will find that all friction which occurs between an individual and a group, an individual and another individual, or a group and a group, is simply on this basis of disagreement. And this disagreement comes about because of a divergence of decision.

Now, decision is very difficult, sometime, to reach. But this is one of these hidden things, actually, in an argument. You are arguing with somebody. If you will isolate out of the argument the decisions for action or inaction — you see, a decision can be for action or a decision can be for inaction — and if you have selected out the action and inaction decisions which you want effected, the argumentation will be minimal, because you have clarified the problem of interpersonal relations before you have tried to practice interpersonal relations on this problem. You've clarified the problem. "Exactly what do I want this person to do?" or "Exactly what do I want this person not to do?" And from there you base your arguments.

Now, if it comes to a pass where it's very important whether or not this person acts or inacts as you wish, in interpersonal relations one of the dirtier tricks is to hang the person up on a maybe and create a confusion. And then create the confusion to the degree that your decision actually is implanted hypnotically.

The way you do this is very simple. When the person advances an argument against your decision, you never confront his argument but confront the premise on which his argument is based. That is the rule. He says, "But my professor always said that water boiled at 212 degrees."

You say, "Your professor of what?"

"My professor of physics."

"What school? How did he know?" Completely off track! You're no longer arguing about whether or not water boils at 212 degrees, but you're arguing about professors. And he will become very annoyed, but he won't know quite what he is annoyed about. You can do this so adroitly and so artfully that you can actually produce a confusion of the depth of hypnosis. The person simply goes down tone scale to a point where they're not sure of their own name. And at that point you say, "Now, you do agree to go out and draw the water out of the well, don't you?"

"Yes-anything!" And he'll go out and draw the water out of the well.

The introduction of decision is also the end and object of war. It is an unsuccessful war which is fought without that. Any war fought without that as an object or an end is an unsuccessful war. Really, there isn't too much wrong with war, but there's a great deal wrong with waging war with no end in view. So that's just enMEST.

Clausewitz, in his great treatise back in umpteen-umpde-umph, has something to say about war being a method of persuading the cooperation and more closely allied views on the part of some other country, said persuasion being by force of arms. That is not exactly the way he stated it; but he used a paragraph about that long.

Anyway, force of arms is what you use in order to make a decision take place.

Now, this country goes out and anchors all of its battleships in Pearl Harbor, you see, and says, "Well, there we are." They made no decision about the war. And we fought a war from 1941 to 1945. And the end product of that war was national apathy and near economic collapse.

The youth of this country today have no feeling whatsoever for any further action along any line. You take your eighteen-year-old boy today: no goal. If he starts out in any line, the army is going to get him. If the army is going to get him, that's just silly. That's going to be silliness and so forth, so he's just in apathy about the whole thing.

There's no cause there at all. He lived through a period of 1941 to 1945, of a war being fought with no end in view.

And the war — if you’ll notice, wars follow a tone scale. The war of 1917-1918 was fought for a specious reason: “to make the world safe for democracy.” Bull.

Then people tried to find other reasons why we fought the war. And they said the reason why we fought the war was because J. P. Morgan had issued an enormous number of bonds and we went to war to defend J. P. Morgan’s bonds. And then they said there were other reasons why we went to the war, and there were other reasons why we went to the war and there were other reasons . . . But they didn’t have a reason.

The propaganda reason was to make the world safe for democracy, and what sprung up in Europe in its immediate wake? That which sprung up in Europe was the immediate lie to everyone who had believed that we made the world safe for democracy. Because in the wake of this war which we fought and secured in victory was fascism, communism, every kind of political buffoonery known. Europe became a slave state following this war.

And so people found out they didn’t fight that war for a reason or to introduce a decision. That war was not fought for that reason. And a deterioration of national culture ensued, because a war is a violent thing. And if it has a maybe in it, it becomes a national engram.

The Spanish-American War was not a national engram. That was a very interesting war. It was a short war, but that wasn’t why it was passed so easily. Well, we went down there to make Cuba free, and Cuba got free — wham. That was all there was to that. No maybes.

In 1918 we were making the world safe for democracy, and we didn’t and everybody knows we didn’t. So we said we were and we weren’t. And so we didn’t introduce a decision into anybody’s mind by the force of arms. After an enormous expenditure of men and materiel and a complete disruption of national economy, we had failed to introduce a decision. Well, that’s just that. So it was a maybe.

So we come up to 1941, and from 1941 to 1945 we don’t even bother to announce a decision. We didn’t even have a phony one. And now look at the national culture. You know, we’re sort of — kids are all down along the line. We had, for several years, the world’s most powerful weapon, exclusively. All we had to do was bark and every nation on the face of the earth would have jumped. And instead of that, they barked and we jumped. And we have jumped and jumped and jumped. And now everybody’s got atom bombs. Now we can all have fun.

You see the irrationality of it. It has wound up the aberration of the society into a confusion, because no decision was ever introduced for the last two wars.

I’m only citing this, not as an example of Group Dianetics, but only as an example of interpersonal relations. There is nothing wrong with you going to war with another human being or a group as an individual. There’s nothing wrong with you being one of these nasty, snide, decisive characters that somehow or other gets his own way.

When you were a little kid they told you, “You’re not supposed to get your own way, you can’t always have your own way and you must adjust to the fact that you can’t always have your own way because you can’t always have your own way. Get down tone scale, kid. Let’s go a little bit lower. You can’t have your own way, you can’t, you can’t, you can’t.” And finally he grows up.

You’ll find a person has to be pretty well up the tone scale in order to commit decision, because committing decision often goes into the commission of an overt act.

There’s nothing wrong with you being right. And there’s nothing wrong with your exerting that rightness on a wrongness in order to get a complete agreement on rightness. There is this factor, however, that you shouldn’t pick people six feet six inches tall to exert this force of arms upon unless you’ve got a club. And that’s a rule I’d like to have you remember.

But in the course of interpersonal relations, you will find two people trying to resolve a problem, usually, in this society, and they try to resolve the problem this way: “Well, I don’t want . . .”

And the other one says, “Well, I don’t want . . .” And then this one says, “Well, I wouldn’t want . . .” And the other one says, “Well, I don’t . . .”

You know? They’re not going to solve anything. They’re going to get a government bill or something out of this — nothing constructive — because each one is saying “I don’t want” and “I won’t be.”

“I won’t be.”

“All right, I won’t be.”

“Good! Neither of us will be. Hooray!”

You will find the last time — I’ll just make this venture — the last time that you had a little clash with another human being, neither of you won. Neither won. Possibly both of you said “No.” “No.” And if you went around now and discussed it very thoroughly after you found you’d given up a point, if you went around and discussed it with the other person, you would find that a much more active decision could have been reached.

You very often have forsworn something in the society. You’ve said, “Well, I’ll do without so that he can,” something of the sort. And you go on doing without — nobly — and doing without and doing without. And after a while you find out, shockingly, that there wasn’t any point in it. That’s very upsetting. The other person didn’t want you to do without. And as a matter of fact, the other person starts tearing his hair out eventually and saying “Please don’t do without! Please.” “I never expected ., . I don’t want it,” and so on. Big rift occurs at that moment.

The best way you can help people is by very thorough action — not doing without, giving away an inaction.

Power of decision applies, then, between two people on interpersonal relations, since they decide something and become a group on that decision. And the moment two or more people have decided upon something, they are a group 80 far as that decision is concerned. And that’s something you should mark very well. They become a group about that decision. And the strength of that group is a measure of their survival. Therefore, it had better be a strong decision.

So mincing words with social lies does not reach the point of a strong group or a decisive action. It gets nothing done. Reaching a low point, then, is bad, and a high point of decision is good. But in order to reach a highpoint of decision, you will find out you often have to be very punitive, very decisive, and that the action you envision must be capable of being effected. And if you follow those rules, boy, the people that combine with you will be a pretty strong group. The power of decision is actually the power of sanity. And just as you can run away and then become afraid, as well as become afraid and run away (it works both ways, you see: you can become afraid and then run away or you can just run away, and by the action of running away become afraid, because you’re dramatizing being afraid, so you will agreeably become emotionally afraid), so it can work that simply by being decisive, you come way up tone scale. You just artificially get decisive. You come up tone scale. In other words, don’t look at this — don’t look at this now as “The only method of being decisive is to come up tone scale and then be decisive.” No, there’s another method. And that is get decisive and come up tone scale.

If you just mercilessly search out of your life, in the actions and the common actions of your life, all of the maybes on a decision level, and if you suddenly assert your decisions where you have withheld decisions, I can guarantee you that your life will smooth out pretty well. If you do that in a big office, for instance, where there’s a big staff, it may very well be that by asserting your decisions they fire you straight out the door. That’s where you belong, then. You’re a lot better off outside that door. If this environment has smothered your power of decision, you don’t belong in it. Most of the indecision which you will meet in life is strictly based around choice of environment and the ability to exert decision in that environment.

There is a therapy, all by itself, of placing a person in another environment: environmental therapy. Merely by changing the environment you bring the tone up of the preclear. If you’ve seen a preclear in somebody’s home — this preclear is in somebody’s house and his power of decision is being nullified continually in this house — by moving him to another house, you will bring him up tone scale to a point where he’ll run much better.