Very few people are sufficiently aware of the great importance of emotion in processing. If you could take all of the painful emotion off the case you would have a release. Of course, on a practical line, it is very hard to pick up all the emotion without picking up physical pain engrams as well. It so happens that every painful emotion engram sits on a physical pain engram; nevertheless, if you could take all this emotion off the case you would have a release.

These various factors were not coordinated until we got the triangle of affinity, communication and reality. At this time we were able to coordinate the problem and get some solutions.

The front part of the Handbooks has in it a two-dimensional tone scale, but the tone scale is actually three-dimensional. It is actually a stack of triangles. Beginning with the base triangle, they go up on a sort of a geometric progression.

By making this into a three-dimensional scale, it suddenly becomes a great deal more useful. By examining this closely we can begin to understand a little bit more about emotion, and we will go into that more thoroughly later.

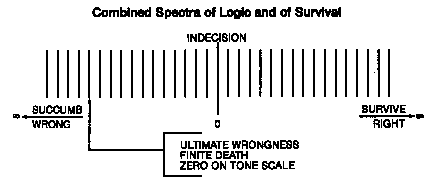

The next figure we have is a figure which is the most prominent part of a subject known as Dianometry, the measurement of thought, which is concerned with how people think and what logic is. And in order to understand this, one needs to know a little bit about the history of logic.

Once upon a time, man functioned on one-valued logic. You can see immediately that one-valued logic would be highly reactive: cause and effect, and that is all. But cause and effect were not determined by man to be within man. Cause and effect were exterior to him as far as he could tell. This was one-valued logic. Sum it up to the will of God. Anything that happened was God’s fault! That is the logic of some savage in the jungle. If he gets his feet wet, that is God’s fault. And if he dines too well upon slightly decomposed whale and gets a stomachache, that stomachache is God’s fault. That is one-valued logic. This is a fundamental in reactive thought.

Then a man by the name of Aristotle codified logic. He said in effect that man has a right to think; he has a right of decision. That was a very great advance. Of course, men had realized this long before Aristotle, but he said so, and he gave us two-valued logic. That was a considerable contribution to the field of logic.

So here was two-valued logic, right and wrong — in other words, an absolute scale. There was no in-between about this. Something was absolutely right or it was absolutely wrong. This system fits in with law and religious connotations very closely, in that an action is either good or bad.

In a practical world you really can’t deal very well with two-valued logic, and yet you will find today as you look around that most people — particularly the illiterate peoples of the world — have advanced in the culture up to two-valued logic: right and wrong, God and the devil. It’s either constructive or it’s destructive.

A girl kisses a boy — is that right or wrong? Now, you would say, “Well, it depends.” No — that’s wrong! “A girl gets married and has children” — right or wrong? You might say, “Well, I don’t know, some of these things don’t work out too well.” Not in two-valued logic — that’s right! There are just these two values at work.The engineer in recent years found himself unable to work with Aristotelian logic, and as a consequence he changed it around to make it a little more workable. In the first place, he had staring him in the face a mathematics — Boolean algebra. Boolean algebra figures out all answers just in terms of yes and no. As a matter of fact, you can evolve all mathematics in these terms. “Is yes greater than no, or no greater than yes?” The brain, particularly by engineers who are accustomed to working on switchboards, is considered to work wholly on this basis of the yes is greater than the no. In other words, it’s hotter than it’s cold; it’s redder than it’s blue — yes, no, yes, no — except that the engineer in actual practice doesn’t use that. He uses three-valued logic. More values in logic are being introduced in direct ratio to the advance of the culture.

So the engineer says right, wrong and maybe. That middle one is maybe. He had gotten up to the point where he felt that there weren’t as many absolute values in the world. A car could be a good car, it could be a bad car, or maybe it wasn’t a good car, and maybe it wasn’t a bad car. As a matter of fact, it is very hard to think without using a maybe occasionally.

This evolved to where we End out that the second we really begin to regard the human mind, it is absolutely necessary for us to regard logic in infinity values. We immediately take a jump from three-valued logic into an infinity of values. And actually we come upon, then, a highly workable system of logic.

What we are dealing with here is a spectrum — a graduated scale. There are lots of these graduated scales in Dianetics. One of the basic principles of thought that we use is that there is no such thing as a completely sharp value. There is a graduated scale.

Here is a series of lines. In the center is zero, and to one side of the scale is right. That has an infinity value and that is survive! If anybody got completely, absolutely, infinitely right on anything, he of course would live forever and so would the universe, and so would the whole universe of thought. That gives you an idea of the incredibleness of being completely and absolutely right without a single wrong factor anywhere! An infinity value of right on any one solution would be immortality.

All the way over the other way is wrong, and on this side we have succumb. The scale goes out more or less to infinity in this direction too. Actually, you can argue about the infinity over on the wrong side because how wrong can a person get? Dead. That is how wrong he can get on anything.

So, from zero on this ladder of lines to the right we get a tendency toward immortality, a tendency toward survival; and going left on this infinity of lines we reach being wrong.

The reason there is an infinity on the wrong side has to do with the whole universe of big theta and the universe of little theta. A man isn’t very wrong as far as the universe is concerned when he is dead. He is very wrong where he himself is concerned, where his own race is concerned, his own group and his own family. He is even wrong where mankind is concerned. But of course he is also partly composed of MEST, and if he was completely and utterly dead, this MEST would be dead too. If MEST ever got down to a point where it was dead, that would impose a stop, because if MEST died out like that, that would be the universe stopping; that would be the end of the universe.

A person dies by degrees. First, he dies as far as little theta is concerned, and then, little by little, cellular death sets in, and the last living thing in him probably is his fingernails. When they finally die, you can say the person is all the way dead. This takes about a year and a half normally. That gives you some sort of an idea of where zero is located on this scale. It is not quite where you thought it was. But if the energy of which those cells are composed died off, that would be the end of the universe.

Now, I’m salting this material down with a few little philosophic imponderables, but we find that this equation is very valid. We have here a thing which will graph logic and shows, more or less, how the mind operates.

You could call this the central board of the mind. This would be fed literally by thousands of such evaluators. This is the computer by which all the data of the problem is summed up.

Did you ever see a Chinese abacus? They knock the little wooden pellets around on this board. This is not a child’s toy. You will see these things in Chinese banks, and mathematicians building ships use them to figure out all sorts of things. They will pick up an abacus and start knocking the wooden pellets around on the thing, and they will say, “Well, the square footage is 928 on this.” You look at it and there isn’t anything resembling a 9 or a 28, or anything else. It’s a wonderful thing — they give it to children to play with in the Western world! But what it is, is something to keep tally on the brain. The mind does the computation and all the Chinese does is use this thing to keep tally on what he has thought of before. He is using the human mind as a servomechanism in his mathematics.

Some mathematicians try desperately to tell you “Mathematics is pure. It existed before man got here, it will exist while he is here, and it will exist long after he has departed. It is a pure science.” That is an interesting point but it does not happen to be provable.

It is fine to put a mathematical formula down on a piece of paper and place it in the middle of an Egyptian tomb, hoping it will stand by itself, but it wouldn’t be any good to anybody until the human mind addressed it.

We cannot escape the fact that the human mind is a servomechanism in all mathematics. We can’t divorce any of man’s activities from his mind. When a man examines any problem, this central board of the mind — somewhat on the order of an abacus — will go into operation and keep tally, and this is the way he makes a decision.

One could say that a person feels perfectly null about things, his mind is sitting about zero. (The mind never does this, however; it always picks up from where the last problem left off.) He isn’t quite sure what he is going to do. Suddenly he decides that he is going to eat dinner. Well, that’s fine. It is something to do; it’s a decision. So the arrow on the spectrum will start to work and he moves over to two lines right about eating dinner. But he thinks about it for a moment, and he is not hungry. He doesn’t want to eat now. This will pull him right straight back to zero again. Should he eat dinner? Shouldn’t he eat dinner? Indecision!

The next thing that he thinks of, perhaps, is the fact that he wants to go to a show at seven o’clock and it is now six. So if he wants to eat dinner before he goes to the show, then he had better eat dinner. That moves out there to two values right again. And then all of a sudden he thinks about this place that serves beautiful duck, and he thinks to himself, “Gosh, the last time

I ate that duck — oh, boy!” So that’s a few more values right. Then he reaches into his pocket and finds out he has only got fifty cents. So to eat duck is pretty wrong, and he comes back toward an irresolution again. Where is he going to eat? In other words, is it right or wrong? Well, that’s one of these little indecisive, undramatic problems that a man solves all the time, and he solves it by these lines.

Let’s take two people who have had a lover’s quarrel, and the man thinks he ought to call the girl and apologize. He hasn’t made any big decision till he starts thinking about it. Then he says, “I think I’ll call up and apologize. After all, I love her dearly, and that’s what I’m going to do because by apologizing, everything will come out fine.” This action is six values right. But then he thinks, “But she told me I was a cad!” That really affects him and he thinks about it for a moment. “A cad, yes, she said that.” So to call her up would be eight values wrong. (We count back from the last arrow.)

Then he thinks, “But Oscar is liable to call her up and she is liable to start going out with him, and I couldn’t bear that. I think I will call her up.” Just the thought of Oscar is pretty bad. That makes it immediately ten values right to call her up. He is getting up there to a point where he is going to call. As a matter of fact, he could make a decision and call at this moment, and he does make the decision and call but he finds out that her phone is busy.

So he immediately says, “It’s that Oscar!”

Now he gets a little bit more upset about it, and here we have got some more values right, and this means he is going to call her or else! As far as he is concerned, the right solution is to call.

So he calls her and finds out that she has already made a date with Oscar, that she is off with him for life, and that she was just sitting there at the phone waiting for him to call so that she could show him up.

Immediately, as far as this problem is concerned, he recaps after the act and says, “You know, that was about twenty-five values wrong.” Boy, is he wrong!

You can add up all of these problems in this fashion: how many values right and how many values wrong? We must then include something in all thinking: the evaluation of a datum. What is the value of the datum? How many values right and how many values wrong in relationship to the importance of the problem? The mind works these things out all the time and it can assign values; it has sub-computers that are handing up values to this continually. How many values right and how many values wrong? Back and forth the little arrow travels, and the person will arrive at a decision.

When people are indecisive, their computer is sitting dead center and you are getting no action. A computer which continues to sit dead center with no action gets an accumulating energy level behind it, and something is bound to happen. Something will break with this sooner or later. A person could actually have a type of engram that says “You can’t possibly make any decision. You don’t have the power of decision. You don’t have any will power. You never can make up your mind,” which would actually force the evaluation to sit in the center indecisively, and such a person wouldn’t be able to think easily.

Then there is the person who has got an engram that says “I am always right. No matter what I think of, I am completely right. I’m right all the time.” This freezes the computer over on the survive side all the time. He doesn’t have a chance to evaluate his problems because he says “I’m right.”

He thinks, “Well, the thing to do is to take this Ford car and drive it off a cliff,” and he is right so he does it. Of course, that would be psychotic, and that is what is the matter with a psychotic. His evaluation scale is stuck in one place. He can’t think. He can’t evaluate problems. He can’t make decisions.

A person who has an engram that says “I’m wrong, I’m always wrong, I’m never anything else but wrong!” starts to think out a problem very logically, but there will sometimes be enough false data entered into such a problem by the computer itself to make him wrong — because he has to be wrong. That is an interruption of thought.

So fixed values can enter into this computer circuit and prevent the person from evaluating his information properly, and at that moment he stops thinking well or easily. Engrams assign fixed values to practically everything.

For instance, someone says, “I’d like to get married. She’s a beautiful girl.”

And the engram says, “You hate women. You know you hate women. You don’t want anything to do with women!” So he doesn’t get married.

Now, supposing he has data in there that says “I can’t believe it”; every datum has to be distrusted completely, so he could never have a sharp assignment of value to any datum which he has. He can’t believe it. He wouldn’t be over on the survive side.

A person who has “I have to believe everything” of course has the same trouble. It is just as much a fixed value. Everything he adds into the equation, even somebody telling him black cats are always green, has to be believed!

People who have a hard time with their sense of humor may or may not have an engram that says “You have no sense of humor,” but that’s not what causes it. The thing says, “You have to believe it,” and humor is actually a rejection of material. The material comes in; it is thought to not compare with the real world and one rejects it — boom! Out it goes again. But if the person has to believe it, you can tell him a joke — you say, “Well, Pat and Mike are walking down the street, and they stop in front of a jewelry store window. Pat says, ‘Boy! I’d like to have my pick!’ and Mike says, ‘By God, I’d rather have my shovel! “‘ — and the fellow just looks at you fixedly: “Pick and shovel… Were they workmen?” He’s like the Englishman that lay awake all night trying to figure the joke and it finally dawned on him!

That is the person who can’t reject it; he has to believe it. Now, if you give this person a release in processing, you are liable to trigger this, and you will observe the strange process of him laughing at all the jokes in his life that could never be evaluated or laughed at before. They will actually come up on a whole chain — literally hundreds of thousands of jokes and funny quips and sayings he has read in newspapers and so forth.

Now, because he learns that it is socially bad not to have a sense of humor (this is something for which he may be indicted before the court of his group), he will watch the people around him fixedly, and when they start to laugh he will laugh. You can catch someone that way by telling him a story. You say, “A fellow walked into the restaurant with a big dog, and he sat down at the table and the dog sat down at the table alongside him. The waiter came up and the fellow said, ‘Now I want some apple pie and a bowl of milk for my dog.’

“The waiter said, ‘All right, sir,’ and went away.” (This person will be watching very earnestly.) “Then the waiter came back and he said, ‘Well, sir, we have a bowl of milk for your dog, but we have no apple pie. Would peach pie do?”’ and you look very bright at this point. The person will look at you distrustfully for a moment and then burst out laughing!

If you want to find a “You’ve got to believe it” engram in anybody, spring that joke on them. If they laugh, they’ve got one, because the person has had to learn to laugh at jokes socially although he doesn’t actually think that any jokes are funny.

Somebody can say to such a person, “The best thing for you to do is to divorce your wife.”

He will think this over for a while. “All right, so being married is wrong. Shall I divorce my wife? Well, I have to! Being married is wrong.” That is an exaggerated level of activity, but you will find that there are people like that who are impressionable and suggestible.

That is exactly what hypnotism is. Somebody else is taking a point on the person’s computation scale and moving it around. The person himself doesn’t think; he has somebody else moving the arrow around for him. When it approaches the complete fact of this being done by somebody else, the person is either in amnesia trance or under hypnosis, or he is insane.

To arrive at correct evaluations one has to have the right to make decisions. An engram is fixed data; it does not allow evaluation. For instance, a forgetters such as “It is not to be thought of” sends intelligence down, and a man gets more and more wrong in his decisions. And how wrong can a man get? Dead wrong.

Now, if we take the right-and-wrong board and we put it together with the tone scale — the stack of triangles — we find out that they are the same thing in operation. This board could have an immediate value for one datum, or it could have a value for the whole person. A person could be, let us say, consistently and continually wrong. This would mean he would be rather depressed. And if he was continually wrong and nobody would let him be right, he would be in a state of apathy — tone 0 to 1.

Zero is finite death for the individual, for the group, for the future, for mankind. This scale could operate for anything or anybody or any collection of beings. Infinity would go on down further, but this would be talking about universal survival. We are not interested in universal survival because it is rather impractical. We know when a group is dead, it is dead. We know when a man is dead we bury him, and the rest of the universe can go happily on. It has no further bearing on him, if you consider death in that light. So we don’t need to worry about the infinity value on the wrong side of the scale.

All of this has to do with emotion, and it also has to do with computation and perception.

If a man is almost all the way wrong, he becomes rather fixed as to what he thinks he should do. In other words, he is so close to dead he actually begins to approximate death — and that has a certain survival value all by itself. The opossum has borrowed part of this tone scale — the pretense of death. Everybody says he is dead, so he is dead.

A man will go into the same state. On the field of battle, a soldier will very often fall down without being hit at all. He is in a complete fear paralysis, he can’t move. They call these people catatonics, and there are various classifications of insanity that come into this bracket. That would be a permanent state on the scale, for the whole being.

We find out that a person who is in a fear paralysis would not be able to perceive very much around him, and he certainly wouldn’t be able to communicate with you. That is the trouble that we find with the catatonic in the institution — we can’t talk to him and he can’t talk to us. He is out of communication. So his communication is down very close to zero.

As far as reality is concerned on this scale, we know that we have agreed upon certain realities in the field of the mind. So actually this reality all the way down the line is agreement. We have agreed upon a reality as far as the world of thought is concerned. We have agreed that this is real, and so it goes on being real. We can see that nobody in a state of fear paralysis has any great sense of reality. He is not dead, but he is dead, and he is certainly not going to agree with you or anybody else. If you could just get him to agree with you, or get him to sense the reality of that fire which you have just built under him, he would move.

But along the line of affinity, if you cannot talk to this man and he doesn’t know you are there, evidently, and there is no concourse or anything else, he cannot feel any affinity for you. And if he can feel no affinity for you, you are not going to pull him up either.

Sometimes affinity can be sort of regenerated, and you can feel affinity for him and he feels affinity for you somehow or other. But it’s pulling him up by the bootstraps, because he is down there at a point where you can’t communicate with him, you can’t establish affinity with him, and he can’t agree with you — he has no sense of reality. As far as the soldier who fell down on the battlefield and is now being rushed off to a hospital is concerned, he is right there at the instant he fell down on the battlefield. That is his sense of reality. He has no concept of the actual reality of his situation. He will be lying in an institution day in and day out with no change occurring. He is still on the battlefield.

Let’s take a look at the affinity lines on this. We have come down to apathy, which is the lowest state on the scale, and when you get somebody in an apathy engram, you have really got something to contend with.

Someone who is working all right in other states may suddenly be triggered into one of these apathy engrams, and he will say, “What’s the use? How could I possibly?”

You say, “Well, go back over it again.”

“What’s the use?” All is lost as far as he is concerned, and he refuses to go through it.

Of course, a person can feel slight despair about things sometimes, but that is not a real apathy state. That is a top order of that state. When a person gets into a real apathy state, you have got something on your hands. In grief a person will sit and cry. But in apathy he won’t do anything. He has approached this level of fear paralysis and death.

Right above apathy, we get grief. Grief is actually the upper part of the apathy band, but it is called the grief band. The 0 to 1 scale has been named the apathy band. Actually, about 0 to 0.5 is apathy; and 0.5 to 1.0 on the tone scale, the upper half of that band, is actually the grief zone. There is where grief is located.

Right above grief we have fear. Fear is getting into the 1 to 2 band. Grief is that emotion which is felt when loss has taken place, and fear is that emotion which has to do with an imminence of loss, perhaps of one’s own life, or of a friend by death or departure. A cut-down of one’s survival potential by a loss: the threat of that is fear, the fact of it is grief, and the accomplishment of the fact is apathy. If it has taken place with great magnitude, the person will go right on down to the bottom of the scale, and if he has nothing in his vicinity to pick him up, he will land in an apathy state and stay there.

This is how a person is moved up and down the tone scale.

Now, there are two factors involved here. There is the kind of emotion — such as grief, apathy, fear — and there is the magnitude. For instance, there is terror, which is just magnitude of fear. Or you could take grief and call it sorrow; grief has to do with a greater magnitude of sorrow. It is the same thing, but there is simply more of it.

Above fear we start to get into covert resentment. Then we get into anger, which is the solid center between 1 and 2 on the tone scale. There a person is still fighting. Something comes in and threatens him with a loss, and this person says “Hrmmph!” and tackles it back again.

It is a strange thing, though, that when that anger is beaten back and defeated the person sinks into fear and grief, and if it is broken too thoroughly he will sink into an apathy. That is what is known as the breaking of an abreaction or, in Dianetics, the breaking of a dramatization. If you break an anger dramatization, for instance, too thoroughly the person is shoved back down the scale, because anger is a breakthrough point.

You will never be able to release anybody if you fail to reach a point of his complete tone where he is angry. One has to go up this scale if he is at all below it on any subject.

There may be a point somewhere in this case where he is saying apathetically, “Well, Mother was after all just Mother. Yeah, I love her very much,” and you have just runs through this series of knock-arounds and beatings, and so forth. Sure, he shouldn’t stay angry at his mother for the rest of his life, but if he has never been angry at his mother, you are lying below the anger belt and this case is not going to recover until he comes up to and through the anger belt on the tone scale; because every case will come up the line, one right after the other, on these emotions.

So he has run across this one where his mother denied him things and did this and that to him, and he is still telling you “Oh, I love her dearly. Yes, I love her dearly, I love her dearly.” He is down in propitiation, which comes below the anger belt. Propitiation starts right down in the neighborhood of apathy. If you get someone who is propitiative, that is very bad. In lots of cases, you can tell where they reach that on the tone scale because they will bring you presents as an auditor. That is propitiation. That is “I’m buying you off. Don’t kill me.”

Anger is above that, but he can never get mad at his mother. Then one day he says, “Oh, if I could just get my hands on that woman, I’d kill her! I’m going to write her a letter, that’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to fix her!” and he mutters around about it. You restrain him from writing the letter, but don’t make it too positive that you are restraining him. You accomplish the restraint of the writing of the letter, because in a few days he is going to come up to boredom and he’ll say, “Ah, well, Ma — she had her troubles.” If you permit him to get that angry at the period when he arrives there on the tone scale, he is going to have a lot to patch up afterwards.

It is very embarrassing to most preclears when they sound off as they come up the tone scale and pass through this anger band. They start telling people off, and then they find out a few days later that they didn’t need to be that brutal about it, they didn’t feel that bitter about it, and now they have actually broken an affinity. Whereas, if they had just left Mama and Papa and Uncle Ezra alone during that period, when they got up above it they wouldn’t give a darn about what these people had done. If Papa were to show up now (Papa used to beat him with a club or something like that), the preclear would say, “How are you? Sit down and have a cup of coffee,” whereas if he had caught him earlier, he probably would have broken Papa’s nose!

Nearly everybody has had their abreaction’s broken by their parents. This doesn’t mean, by far, that all parents are terribly nasty to their children. This is very far from the truth. But your worst cases have had some upset this way, and most parents in this society have broken the dramatizations of their children.

For instance, a child gets mad. Papa has got him sitting there at the table, and the kid is supposed to eat his spinach and he won’t. He says, “I’m not going to eat my spinach.”

And Papa says, “You’re going to eat your spinach, young man, or you’re going to march right straight to your room.”

After all, this guy is not very tall and Papa is a lot bigger, and Papa wins.

It was a bad thing for Papa to win, by the way. You will find it in processing. It will probably come up as a lock because it is not an actual engram, but it has done something to the affinity scale.

The next point above anger is overt resentment. Just above that we start to get varying degrees of “Oh, well, what the dickens is the use? Oh, I don’t care about it much anyhow” — boredom with the subject. Above that, you get relief. There is a surge point.

The reason this is in a geometric progression is because actually that relief point is about halfway up. There are so many degrees of pleasant emotion above the relief point that we don’t recognize how high and how varied that relief point is. We just say, “Well, that’s happiness,” and let it go at that. But that is not the case. There are a great many degrees of being relieved, happy, cheerful, ecstatic and so forth. They go on up the line, and the happiness end of this band is bigger and longer than the depressed end of it below the relief point. So above boredom we have got relief and then happiness. Pleasure and all the emotions of pleasure fit above this point of relief.

These emotions are actually a spectrum where you take little theta, walk in on it with MEST, and start reversing its polarity. The more its polarity is reversed, the more MEST there is and the less theta, until you get down to the bottom where the person is all MEST and no theta; he’s dead. You start up the line again and you get a little bit more little theta and a little less MEST, until you finally get clear up to the top of the spectrum where you get pure survival, pure life, pure little theta.

This is what the Hindus are talking about when they refer to real saintliness. A real saint gets up to a point on this tone scale, according to the Hindu, where he becomes so much “all thought,” so utterly and completely pure, that he sort of nebulizes on the spot and takes off for heaven in his own body. It is rather amusing that as we look at this thing hypothetically, that happens to be true!

At the bottom of the scale he is all earth and clay — dead. Further up he is resenting being overcome and is angry about it. And up the line he starts to win. That break point occurs when he is about fifty percent little theta and fifty percent big theta. Up above that point, the amount of big theta starts to fall away and the amount of MEST would theoretically start to drop out of the picture.

Actually, what happens is that he is more and more able to control the material universe. He is more rational, he can think more easily and ably, he doesn’t make mistakes, and he begins to control the material universe more and more and more. He also has no residual physical error, so that probably his longevity increases markedly.

Though little progress has been made in the field of psychic phenomena in Dianetics, we have made enough progress to raise the hair of the whole society — just as we are doing on the subject of processing. But it is interesting to me that some of the past concepts of what life is seem to be very antique at this time.

We haven’t had time to look up some of the confirmations thoroughly enough, but there is just a little bit more evidence in favor of immortality and the individuality of the human soul than there is against it. The more returns that come in from research, the more it tends over into this — not from any religious data whatsoever, or any religious conviction; it’s just solid scientific results. And it seems to be turning up more and more the point that an individual is a continuum of life and activity, regardless of his own body.

We have got someone who is doing nothing but slug into this right now, and he is working hammer and tongs. All he is doing is assembling evidence.

The preponderance of the evidence is in favor of individual immortality. I never thought that would be the case. All my life, I had supposed that when a person was dead, he was dead. He looks awfully dead! Actually, that was all the scientific evidence the society had on that basis a few short months ago: “He looks awfully dead.”

So, we look and we find that this affinity line is the emotional scale of the individual and that is what you are addressing. Now we find out something very important, that when you are unable to get any grief off an individual, you can even go to a point and start running relief. You can start running moments when he was bored. You can then run a few moments when he was angry. Then you can find some periods when he was afraid, and pick up a lot of those incidents, and the first thing you know, you will be able to pick up an incident of grief.

You don’t go into these cases and say “Well, we want some grief. ‘The file clerks will now give us the grief incident necessary to resolve the case. When I count from one to five and snap my fingers, we’ll get the grief.’ Well, this guy doesn’t cry; let’s go to basic-basic.” That is not good processing!

Where you will actually enter this is probably in the field of fear. If you can get some incidents where the person was afraid, particularly an incident where he was terrified, you can move down into grief.

A person’s emotions can be locked up anywhere on this tone scale and frozen. You can get a stet emotion, in other words, and it can be set somewhere on the tone scale in some incident in his life where the bulk of his emotions are wrapped up, and it is not necessarily grief. It can be terror.

These are the interrelationships on this scale.

Then we have the tone scale on the reality level. That has to do with a person’s ability to compute, to agree, to get into agreement, to get into his standard bank — data on what reality is and so forth; and to find out how this data may agree within the world and with others. There is reality, and reality does one of these reversals right straight down the line until you get down to zero reality. In other words, he starts converting reality over into other things.

It starts to get very erroneous below the anger level. What would be anger level on the emotional side would be an error level on the reality scale, which would be the logical scale — the logical concatenation.

Over on the communication side of it is the person’s ability to perceive. Did you ever hear of anybody being blind with rage? Well, believe me, they are, because right about that point they stop perceiving. They also stop communicating. They just sort of put out ergs, and they go on down the line, communicating less and less, until they don’t communicate at all. And as they go up along the line from there they can communicate more and more and more.

Actually, that communication can be terrifically aberrated. A person can have an engram which tells him that he has to talk continually. If he has such an engram, he is not in communication. He is talking, sure, and he may appear to listen, but he isn’t. He is out of communication.

Communication is a two-way affair. It concerns also whether or not a person can receive communications, not just whether or not he puts out communications .

As a person goes down the scale, his ability to put out communication and to receive communication deteriorates. His sense of reality, for instance, goes down and at the same time his perceptions will go down, although they don’t go down evenly.

But if we find someone who, for instance, doesn’t have any sonic or vision and his sense of reality about all this is very poor, we will find out that his affinity level is bad as well. These three things are poor simultaneously. They all work one with the next.

On this affinity scale, we have the emotional scale. How does he feel toward his fellow man? You would be absolutely amazed to find out that most people are in fear as far as their fellow man is concerned — they are a bit afraid of him; whereas the only real proper protection that a person could have would be way up the scale. The higher you can get up this scale, the less danger men are to you.

These have been pointed up as philosophic, metaphysical and mystical principles through the ages, yet they are pretty simple when you take a flat look at them. Naturally if a person is afraid, he is going to do things to protect himself; in protecting himself he is liable to hurt somebody else, and if he hurts somebody else they are liable to hurt him.

What is the least optimum method of surviving? It would be going around protecting oneself all the time so that he wouldn’t be hurt; so he has to hurt other people so that they won’t hurt him — only they do because he does! There is an interaction.

This data on the triangle and the tone scale is data which you can use. You can see immediately where a person actually is on the tone scale, both as to an incident and as to the whole being. You can look over his computational ability, his emotional scale (his affinity level), or his ability to perceive and you will see where that person is on the tone scale.

Because we have an interaction like this, we have some sort of an idea, from the performance of this man, what his possible dynamic is. One of these days we will have a fine way to measure a dynamic.

If this person is all shut down on perception, know that his affinity level is low, too. Know also that his computational level is fairly low. But if this person is still being successful, realize you have got a man!

To the individual whose native tone scale is very high, you add the reactive minds scale to his endowed scale, divide them in half, and you will get your average tone scale between the two. You will get approximately where the person is seen to ride as an average. It is usually somewhere in the neighborhood of 2.2 to 2.3, and that is the whole tone of the aberrated individual. That is the way you could compute it. Now you have his whole tone.

A person would vary on this tone scale by endowment. It doesn’t mean that the blank, unaberrated, uneducated individual would simply have, automatically, an infinity value on this whole tone scale. He wouldn’t; his lifetime has been modified by his genetics and other things. But there would be the individual, and then you would have where his reactive mind lay on this tone scale, and between the two of them you get where he actually is in relationship to life.

When you pick away the reactive mind scale, what you have left will be the fellow cleared, and you will get his tone level lifting all the way across the boards.

This means that some people natively are able to communicate better than others. Some think better than others; some feel more affection and so forth than others. These positions have to do with endowment. There is a tremendous difference of personality from person to person.

When you start an individual in processing he has a certain ability to perceive the world around him, to measure present time, to think and remember and so forth that is determined by the whole tone of the individual plus his reactive mind. But when you are processing him you are inspecting just one thing, his reactive mind tone scale, because you are after engrams. And the engrams, as you start down the track, will become very, very apparent to you. You will find out that his sonic is probably off. That’s normal. This is why you should be very careful to balance every case in the last part of your two-hour session. You bring him up to a pleasure moment and run it very thoroughly, then bring him up to present time and put him on straight memory over the whole session. You want him balanced out as the average individual. You don’t want your reactive scale having more weight in his life than it ordinarily would have.

This last step is something added to Standard Procedure beyond what has been written before. You finish up every session by running one or more pleasure moments, and then complete the session by using straight memory on everything which has taken place during the session, leaving no occlusions whatsoever. Doing this, you will have a much more stable preclear

If you can’t run current pleasure moments, run future pleasure moments whether they are imaginary or not. Usually they are just imagination, but you will occasionally find somebody who says “This is really going to happen.” That is quite all right. Don’t invalidate his future.

That is Standard Procedure. Do it and you will find your preclears more stable.